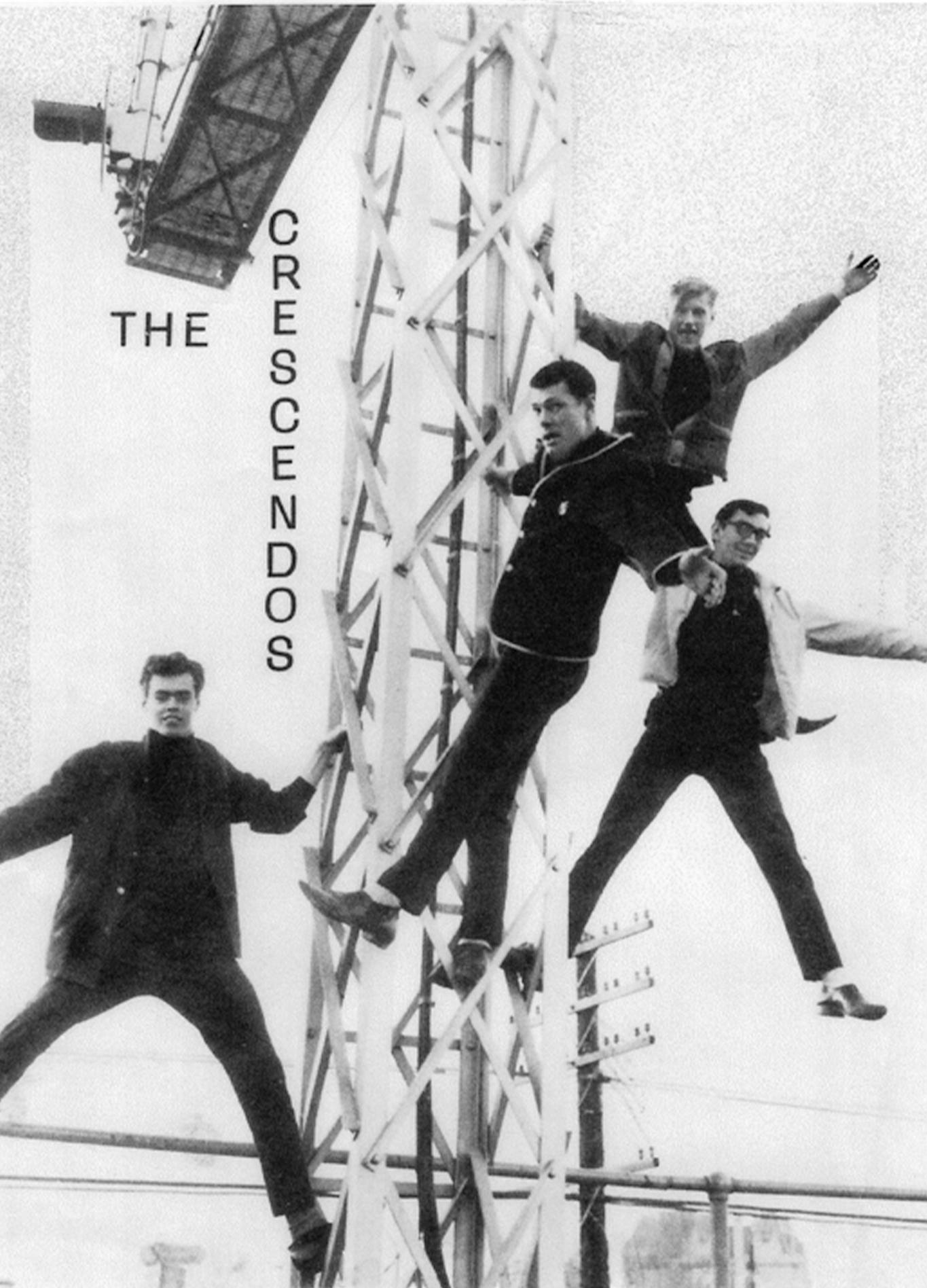

The Crescendos Invasion

Volume One, Chapter Seven

Vance Masters steps out of the Hudson’s Bay department store and is about to make his way across Portage Avenue when he bumps into his buddy Dave Romanyshyn. Dave’s well-known in these parts as the piano player with the D-Drifters. The D-Drifters are popular, working steadily at weddings, socials and the local bar scene, but they’re not Crescendos popular, not to the teenagers. And as Dave’s about to find out, they’re certainly not Vance Masters popular.

They’re standing at the corner waiting for the light to change when suddenly they’re surrounded, by young girls, six or seven of them, then six or seven more. It’s almost as if they’ve been here watching and waiting for someone like Vance to show up. (It’s not a coincidence. Fact is, the Bay’s Paddlewheel Restaurant is a well known hangout for teenagers and... musicians.) Some of the girls are carrying little Brownie cameras, or their Crescendos photos; some are waving autograph books at Vance.

“The questions, many more than I can remember, came so fast,” Dave Romanyshyn would write some years later. “Rat-a-tat-tat... All Vance could do was pose, smile and sign.”

Vance, where do you buy your clothes?

Mr. Masters, what’s your favourite song to perform?

Vance, will you grow your hair longer?

Mr. Masters, do you like the Dave Clark Five?

Do you collect records?

Can you sign this To Linda with Love?

Vance, where do you play tonight?

Vance, who’s your favourite DJ?

What’s your favourite food?

Do you give drum lessons?

Does Glenn give saxophone lessons

Do you have a girlfriend? Does Glenn?

“On it went without any letup,” Dave writes. “At some point, ‘Vance, who’s your favourite Winnipeg band?’ He slipped me a wink and said, ‘The D-Drifters!’ and points at me. ‘And he’s in the band.’ – the only time he got words in. Suddenly I get some requests as well. My Beatlemania moments! Anyway, they weren’t letting up on Vance and I slipped away thinking, David, you’re not such a big deal after all.”

When the Crescendos first came into being two years earlier, Vance Masters was playing with a borrowed drum kit. A year after that the band is playing every community club and high school in the city. They’re playing weeknights or weekends downtown at the Cellar. They’ve got their own van. By 1964 they’re feeling like they’re living in a movie, something like, oh I don’t know – A Hard Day’s Night?

These guys are ambitious. They want bigger better tours. They want to record. They want more of everything and they’re not getting it soon enough in Winnipeg. “It felt like we’d reached a pinnacle,” says co-founder Glenn MacRae. “Like, where can we take it from here? How do we get to the next level?”

Of course the answer’s right in front of their noses. “Every week there was a new group coming out of Liverpool, appearing on Ed Sullivan, a new record coming out – it was like everything was coming from there. I think the final impetus for us was watching the Gerry and the Pacemakers movie Ferry Cross the Mersey. We went to see that movie together, and we came out of there and said, ‘You know what? We need to go there. That’s where everything is happening.’ And we started stashing all of our gig money so we could do that.” By the following July, they’re ready to leave.

“Most of us had never been out of Manitoba before,” Glenn laughs. “The boat trip itself was an experience. We asked if we could get our instruments and do some practicing. That wasn’t possible, so we just practiced singing in the little rooms we were in.

“We arrived in the evening and they wouldn’t let anyone off the boat until the next morning. Everybody had to go through customs and that kind of thing, so we all stood on the deck most of the night, just looking out over the city, imagining what was going to happen.”

Already it feels like a dream come true. They’re here, it’s real. And like any reality it comes with… obstacles. Our heroes hit their first one that next morning. “We were standing on the deck watching the luggage being unloaded on this conveyor belt, and as we were watching, our amps and all the equipment come off this conveyor belt and smash on to the dock, about a two-foot drop. We were screaming and yelling, to no avail.”

They collect their gear and head for the taxi stand, with no idea where to go next. “No problem,” says the driver. Soon they’re chatting with him, about their aspirations. “All of a sudden,” Vance tells me, “he says, Well, I can get you some dates. I want to be a manager – I am a manager.”

The driver, a young bloke named Brian Kelly, takes them to a bed-and-breakfast, one large room they can share. It’s cheaper than a hotel and it’s right downtown, on Lime Street – not too far from… you-know-where. The boys unpack and head out for their first night on the town.

When you first step into the Cavern Club, Britain’s own Mecca of the rock and roll universe, you already know you’re going to hear a great band. What you might not expect is seeing three or four of them. “They used to run all-night sessions,” says Vance. “They’d start at seven and go all night, a different band every hour.” “We spent the whole night there,” Glenn says, “listening to bands and just going crazy, that we were actually there.”

This is the way the scene works, as the guys soon discover, and it isn’t just happening at the Cavern. “In England, or at least in Liverpool,” Glenn says, “bands would play several gigs, at different venues. You’d do an hour at the Cavern, pack up your gear, jump into a van, head over to another club. Another band would be just finishing there. You’d go on and do an hour there. And you would just gig all over the place.”

One of the bands playing at the Cavern that night is the Easy Beats, a local Beach Boys cover band. They don’t have another gig lined up that night, so after their set they decide to hang around. “We got chatting,” says Glenn, “and when they found out we had Fender amps, which is what the Beach Boys used, they went crazy. They had to see the amps. So the next day they came over to our B&B.”

Just seeing these amps is a treat in itself, but wouldn’t it be great if they could hear them? Too bad, mates – half the tubes are broken, for one thing, and for another, they’re powered on 110 volts, not the Brits’ 220-volt standard. Not to worry, says one of their Easy Beat chums; they know a chap who can do the repairs and get them a step-up transformer so they’ll run on 220.

Things seem to be falling into place quite nicely. And who should come calling the next day but their taxi driver and erstwhile manager, Brian Kelly. “He made a pitch to us,” says Glenn. “Him and his father-in-law had been looking for a band; they wanted to start booking and managing bands. We didn’t know anybody else, other than having met the Easy Beats, so we decided to let him and his father-in-law do this.”

The Crescendos have been in Liverpool for a grand total of three days. They’ve made some fast friends. They’ve hired a manager. Brian Kelly is not Brian Epstein; then again the Crescendos aren’t the Beatles – not yet. Brian’s first accomplishment is getting them out of their one-room B&B and into a decent flat. Then it’s time to get them some work. It takes a while – the Crescendos after all are their first and at the time their only client – but Brian and his business partner/father-in-law Bob Brunskill eventually deliver.

“They weren’t exactly the kind of gigs that we aspired to,” says Glenn. “They were in what they call over there ‘working men’s clubs’ – like what we’d call legions over here. There were some that were in fact legions, with retired service personnel, but a lot of them were union-based – like the plumbers union or ship workers union would have their own little club. These were low-class kind of gigs, not high-paying, but we felt we had to pay our dues.”

The band works regularly enough to stay afloat, but not enough to keep their lovesick bass player Denis Penner from packing it in. In December he returns to Winnipeg, into the arms of his fiancé.

After auditioning several musicians, the band chooses Liverpudlian Stuart McKernan – a bit of a rookie, says Glenn, “but we liked him. He was very eager, and he had the look, he had a real stage look to him. He looked like a British musician.”

Stuart might be cool, and there is a certain novelty to seeing a band from Canada, but that’s only going to take you so far. In Winnipeg, the most popular bands were the ones who sounded most like the records they were covering. In Liverpool, not so, says Glenn: “When we got on stage and started playing Stones tunes and Animals tunes and Beatle tunes, copying the records, it was like, ‘What the hell are you guys doing?’ We realized very quickly that we can’t just keep doing this, copying Little Red Rooster exactly like Mick Jagger did it. Nobody gave a rat’s ass.”

What the local bands are doing isn’t new either – Motown, R&B, the Phil Spector-style girl groups – but they put their own slant on them, much as the Beatles had done initially with their own covers. The writing is on the wall: Whatever you play, no matter who’s tunes they are, if you can’t make them your own you better just go back where you came from. That’s not going to happen, say the Crescendos. They rent a church hall and started practicing. “We were good enough musicians that we were able to pull it off,” says Glenn. “Learning a bunch of songs we absolutely loved, we developed a repertoire that was uniquely ours. As we learned to play Liverpool style, as opposed to Winnipeg style, the popularity began to grow.”

The band gets better and so do the gigs, not through the efforts of their managers. “We were recommended by one of the other bands to Bob Wooler, who was the emcee/booking agent/manager of the Cavern. It was very special. To us it was – we had arrived. But it also opened the door for us to start now getting gigs in the kind of clubs that we wanted to be playing – not working men’s clubs, not legions, not little places.”

Glenn traces all of this back to the band’s arrival in Liverpool and going down to the Cavern and meeting the Easy Beats, all on their first day. “We became friends and they took us around and introduced us to all the other bands and they just kind of welcomed us into the community. And there was absolutely no rivalry. Everybody wanted to help. They wanted to help us get gigs. They wanted to introduce us to the right people.”

Bob Wooler offers to manage the band, but – again, in the words of some good friends – even if Wooler is the Cavern’s gatekeeper, he’s not the only game in town, and neither is the Cavern Club. “We talked to a few guys,” says Glenn, “and they kind of said, well, yes, he’s a huge connection, but you’ll wind up playing at the Cavern an awful lot. So, you know – look around.”

Before long they do connect with another up-and-coming agent – Gerry Jackson, younger brother of Tony Jackson, from the Searchers, another of Liverpool’s top-tier bands. “He was booking more hip places for us, but not exclusively,” says Glenn. “Because we still wanted to be able to play at the Cavern and we didn’t want to shut ourselves out of any gigs.”

Another smart move, guys; you need all the options you can get. “We weren’t on top of the world yet. We were getting more recognition, bigger gigs, but there were times when we’d have no gigs.” When this happens, the Crescendos do what all the other bands do…

Allan Williams owns The Blue Angel, a club downtown on Seel Street, and he was the original manager of the Beatles pre-Brian Epstein. It’s not as prestigious as it might sound, Glenn says. “If you couldn’t get a gig anywhere else and you were desperate, you’d phone Allan Williams and say Do you need a band tonight? Your pay for the night was ten quid, which was the kind of money we were making at the working mens’ clubs. You’d have to start at eight o’clock and play till two or three in the morning. It was the worst gig in town.

“But the redeeming thing about the Blue Angel was that there was an unwritten law among the musicians. Once your gig was done, you’d go down to the Blue, as they called it, and do a set for the band that had to play there, so they could take a break. It didn’t matter who you were, how big you were. There was a hierarchy of bands, of course, but there was no snobbery, there was no such thing as looking down on the minions below.”

No snobbery you say? Well, there’s the night Paul McCartney sits in. “We weren’t playing that night,” Glenn says, “but we were there. He got up and did about three quarters of an hour of Little Richard tunes – and just enjoyed his ass off, just going back to his roots. I also discovered that there were probably a half a dozen other singers in Liverpool that did Little Richard as good as McCartney. We kept thinking, there’s got to be something in the water here.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Raised on Rock and Roll to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.