The probation officer reaches into a drawer and pulls out a revolver. He sets it down on his desk pointing right into the face of Bill Iveniuk, who sits across from him with his mother. “If you stay on the path you’re on right now,” he tells Bill quietly, “you’re going to find yourself facing the barrel of one of these things.” Bill looks at the gun, then the probation officer, then back at the gun.

“Is that what you want, son?”

“No, sir.”

It’s enough to strike fear in the heart of any ten-year-old.

Some of the kids in the neighbourhood were putting together a gang. It was agreed that before you could be in the gang you had to break a window in the church. So they all met at the churchyard after dark, gathered up some rocks, and let them fly. Bill and his family are not exactly practicing Catholics but still… “I didn’t want to get cursed or something – you know, coming from that Ukrainian ghost story background – so when I threw a rock I made sure I didn’t hit a window.”

A week later he gets arrested and taken down to the station to answer to his charges. Somebody told the cops that Bill was the ringleader, the instigator, and that Bill told the kids he’d beat them up if they didn’t break the windows. Bill gets off with a warning, delivered at gunpoint as it were, and two years probation.

Not that Bill’s some little angel. “Well, I was a little wild when I was a kid. I was always in trouble. But we’d do stupid stuff. Like me and a buddy of mine, we broke into a house once and while we were there we made ourselves bacon and eggs. We didn’t take anything, we didn’t do any damage – nothing. We just ate and then we left. We were always doing stuff like that. I’d come home with a big basket full of vegetables for the old lady, I’d come home with a bouquet of flowers for her, and she could see out the kitchen window that I’ve taken them from the yard next door, so she wouldn’t display them in the window, she’d just sort of hide them.”

You could say his probation worked. From that day at the police station on, no crimes will be committed. No more garden raiding. No more flowers pinched. No more gangs. In 1954, when Bill turns twelve, he gets a letter from the probation office congratulating him for paying his debt to society.

Point Douglas in the 1950s is predominantly a low-income working-class neighbourhood, populated largely by eastern and central European immigrants. (Bill’s mom is Ukrainian, his dad is Romanian). The Point sits adjacent to the downtown core to its west; the Red River winds along the south side, rounds its namesake eastern point, and then curls its way northward. Point Douglas also butts up against one of the rougher parts of the city’s north end, Winnipeg’s far larger working-class district and its most ethnically diverse. Its reputation as the city’s toughest and most dangerous neighbourhood is rivaled only by that of the Point’s. The crime rate in both districts is higher than anywhere else in the city, and yes there is violence here, some of it gang-related, yet most of the residents themselves see little of this. For them, life in their neighbourhood is as quiet and peaceful as any of the better parts of town. Everybody leaves their doors unlocked. Parents have no qualms about letting their kids play on the streets long after dark. In the Point, the cops out walking their beat know most of the kids by their first name; when incidents do arise they’re dealt with on the spot.

Of course there’s all kinds of ways you can get your kicks without breaking the law. Bill Iveniuk will explore most of them – not with his would-be gang mates of yesteryear (those snitches!) but with his real friends. He’s been pals with Leonard Kotyk (everyone calls him Kody) since they met in kindergarten. Kody had moved to Point Douglas to live with his grandparents after his parents split up. Billy Schmidt emigrated from Poland with his mother when he was nine years old; Bill Iveniuk was the first friend he made in Canada. Marino Vitalli, a year older than Bill, met him when he was in grade three; he’s been hanging out with Bill and the other guys ever since.

The boys live just a few blocks apart and spend most of their time together, in school and out, all year long. In the summertime they’re at the community club seven days a week, playing football, soccer, baseball, cricket, or just goofing around. They know every inch of the bike trails along the river. On their night runs they’ll sometimes get to sneak up on one of the little hobo villages; they’ll race right through their campfire, sending sparks and flames shooting out in every direction, then ride back into the darkness, laughing and shouting and cheering, before the poor fellows know what hit them.

Winter means hockey, playing every night till nine or ten under a single floodlight shining dimly over centre ice. “I used to use Eaton’s catalogs for shin pads,” Marino says. “Hockey gloves? No, I had those big garbage mitts.” Marino can usually get all the way home from the rink on his skates, hardly walking at all but gliding, following the snow-packed tire tracks along the side streets. During the day, there isn’t much traffic on these roads (not many families in this neighbourhood have cars) and there’s a stop sign at every intersection; people are driving pretty slowly so it’s easy to grab onto the bumper of a passing car or truck and slide merrily along until you slip and fall or the driver spots you. Out behind the Winnipeg Hydro station near Marino’s place there’s a massive coal pile, which, blanketed in thick snow, makes for another wintertime favourite. “It’s maybe thirty feet high,” says Marino. “Perfect for playing King of the Mountain. You’d throw guys down and whoever gets to the top is the winner.”

Spring thaw brings a different kind of joy ride: When the mighty Red River starts breaking up, you can jump onto one of the ice floes and ride downstream a mile or two. The ice is thick and heavy and the floes aren’t yet moving all that fast, so there’s nothing to it, really. You just need to keep your balance and, Marino cautions, try to stay close to the shore.

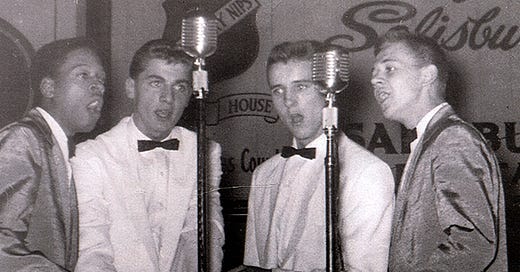

There’s one other thing the boys have in common. They’ve been singing together in the choir all through elementary school. At the annual city-wide competitions, they get to go downtown and perform in front of a big audience at the Winnipeg Auditorium. “We’d have to wear black pants and a white shirt and a bow tie,” says Kody. “You might just get a ribbon or something like that, but to us it was a pretty big deal, and it was fun.”

What does a teenager look like in the 1950s? On television they’re squeaky clean: the parents are middle-class, suburban, sexless, and white: Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, the Donna Reed Show. At the movies, the kids live in a whole other universe: still mostly white but not so pleasant, not so innocent: The Wild One, Blackboard Jungle; Rebel Without a Cause. If you live in Point Douglas, it’s the TV kids who look like aliens.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Raised on Rock and Roll to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.